In part two on my series on Lolita and postmodernity, I will be examining the critical commentary Lolita fashion represents. In order to do so, I think it is helpful to look at two movies- one which deals directly with Lolita fashion, and one which has nothing to do with it.

The first movie I wish to explore is Goodby, Lenin, a German movie from 2003 about the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany. The central plot of the movie revolves around the main character's effort to shield his dyed-in-the-wool socialist mother from the unfolding events of the reunification after she suffers a debilitating heart attack. He embarks on a program of deception to convince his mother that everything is "business as usual" in the GDR, but in the process, finds his own motivation to keep up the charade. The idea is that he is able to rewrite history- to create the country and reunification story he wishes was the historical truth. He is able to reimagine socialism in such a way that it becomes his mother's ideal, instead of the fatally flawed system that eventually imploded in the late 1980's.

In much the same way, Lolita fashion allows its wearers to rewrite history. The fashion of the eras showcased by Lolita, while beautiful, was often a not-too-subtle statement about the lowly position of women in society. The very fact that women were seen as ornaments without human agency is attested to by the impractical, constraining nature of the clothing they wore.

Lolita, to a degree, engages in a rhetorical exercise of "what if" by taking these highly impractical garments and subverting them. Hemlines are higher and more walkable. The preferred fabric for Lolita- woven cotton- is lighter, more breathable, and more practical than historically accurate fabrics. Much of the "corset lacing" that typifies Lolita is ornamental instead of practical, and worn on the outside. While generally a more "modest" fashion, Lolita is not about policing women's bodies, nor is it about exhibiting them in an overtly sexualized manner. While Lolita is by no means "casual" or "easy wearing" attire, it is infinitely more practical and less constraining than the historical wear which inspires it.

One can argue that this amounts to a "Disneyification" of historical dress; candy-coating and whitewashing the very real, and very problematic elements of objectification these styles were fraught with. However, I believe Lolita is more properly viewed as an act of reclamation, taking what was once a mark of servility and sex-based oppression and remixing it as a statement on nonconformity and historical reimagining. In this way, I believe Lolita is part of the "FUBU" school of social reclamation- like the 90's and 2000's streetwear brand FUBU- Lolita is a style "for us, by us"- designed primarily by feminine-identifying people, for feminine-identifying people, irrespective of the male gaze. With the exception of those people who have fetishized such clothing, Lolita does not meet current societal standards of "sexiness" or "desirability". The idea here is that wearing Lolita is a subversion of women-as-ornaments-for-men, and becomes women-ornamenting-themselves-for their-own-enjoyment.

Another way that Lolita serves as social commentary and critique is by creating discursive spaces for the examination of traditional performances of gender, and ultimately the questioning and deconstruction of such performances. An example of this function of Lolita can be found in the 2004 movie Kamikaze Girls, adapted from the 2002 light novel Shimotsuma Story- Yankee Girl and Lolita Girl by Novala Takemoto.

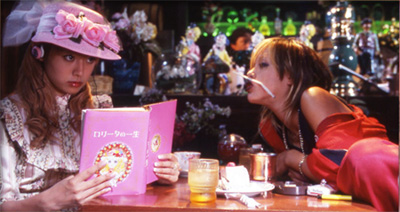

The story is about two teenage girls- Ichigo, the "yankee" or delinquent, and Momoko, the "Lolita". Both girls live in a semirural area in Japan, and are, in their own ways, estranged from the community around them. Ichigo, in keeping with her delinquent status, appears rough, tomboyish, and stereotypically "masculine" in her pursuits. Momoko, by contrast, appears delicate, ladylike, and stereotypically "feminine", as befits a Lolita devotee. However, the movie quickly makes it apparent that not all is as it seems. Under her rough exterior, Ichigo is a gentle soul seeking social acceptance, while Momoko is cold, withdrawn, and singularly focused. The movie ends with Momoko saving Ichigo from angry gang rivals, in a total reversal of the "damsel in distress" trope. The movie is constantly contrasting appearances v. reality, and questioning the validity of gender performance as a means of judging a person's personality.

As could be expected, Kamikaze Girls has a strong fan base in the Lolita community. Aside from the obvious enjoyment gained from seeing one's subculture featured on screen (along with the adorable old school Baby, The Stars Shine Bright outfits), I believe Kamikaze Girls resonates with Lolitas because it is a specific manifestation of the critique of gender performance Lolita makes in general.

Lolita is, in my opinion, a way to express femininity in isolation, or essence, without the cultural baggage. Unlike Momoko, most Lolitas are not "lifestyle", meaning they don't wear Lolita all the time. While most Lolitas will strongly denounce Lolita as cosplay, the truth is that it is an identity they assume- and take off- at will. The fact that there are male Lolitas- some of whom identify as cisgenderd straight- suggests that this is a "portable" femininity they can try on when it suits them. In the same way Ichigo and Momoko "balance" each other in the movie, I believe Lolita is a safe space for individuals to tweak and define their own gender balance. All people exist somewhere on a gender continuum, but it would be my guess that many Lolitas are more gender (and perhaps sexually) fluid than the society at large. Lolita gives people an "anchor" of femininity when they feel they need it, without encumbering them with the issues that surround more traditional aspects of gender performance in today's society. By making femininity an outfit you wear, it subtly critiques the notion of gender as a viable construct.

No comments:

Post a Comment