In part two on my series on Lolita and postmodernity, I will be examining the critical commentary Lolita fashion represents. In order to do so, I think it is helpful to look at two movies- one which deals directly with Lolita fashion, and one which has nothing to do with it.

The first movie I wish to explore is Goodby, Lenin, a German movie from 2003 about the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany. The central plot of the movie revolves around the main character's effort to shield his dyed-in-the-wool socialist mother from the unfolding events of the reunification after she suffers a debilitating heart attack. He embarks on a program of deception to convince his mother that everything is "business as usual" in the GDR, but in the process, finds his own motivation to keep up the charade. The idea is that he is able to rewrite history- to create the country and reunification story he wishes was the historical truth. He is able to reimagine socialism in such a way that it becomes his mother's ideal, instead of the fatally flawed system that eventually imploded in the late 1980's.

In much the same way, Lolita fashion allows its wearers to rewrite history. The fashion of the eras showcased by Lolita, while beautiful, was often a not-too-subtle statement about the lowly position of women in society. The very fact that women were seen as ornaments without human agency is attested to by the impractical, constraining nature of the clothing they wore.

Lolita, to a degree, engages in a rhetorical exercise of "what if" by taking these highly impractical garments and subverting them. Hemlines are higher and more walkable. The preferred fabric for Lolita- woven cotton- is lighter, more breathable, and more practical than historically accurate fabrics. Much of the "corset lacing" that typifies Lolita is ornamental instead of practical, and worn on the outside. While generally a more "modest" fashion, Lolita is not about policing women's bodies, nor is it about exhibiting them in an overtly sexualized manner. While Lolita is by no means "casual" or "easy wearing" attire, it is infinitely more practical and less constraining than the historical wear which inspires it.

One can argue that this amounts to a "Disneyification" of historical dress; candy-coating and whitewashing the very real, and very problematic elements of objectification these styles were fraught with. However, I believe Lolita is more properly viewed as an act of reclamation, taking what was once a mark of servility and sex-based oppression and remixing it as a statement on nonconformity and historical reimagining. In this way, I believe Lolita is part of the "FUBU" school of social reclamation- like the 90's and 2000's streetwear brand FUBU- Lolita is a style "for us, by us"- designed primarily by feminine-identifying people, for feminine-identifying people, irrespective of the male gaze. With the exception of those people who have fetishized such clothing, Lolita does not meet current societal standards of "sexiness" or "desirability". The idea here is that wearing Lolita is a subversion of women-as-ornaments-for-men, and becomes women-ornamenting-themselves-for their-own-enjoyment.

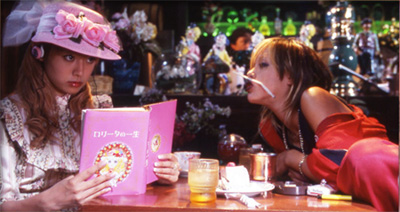

Another way that Lolita serves as social commentary and critique is by creating discursive spaces for the examination of traditional performances of gender, and ultimately the questioning and deconstruction of such performances. An example of this function of Lolita can be found in the 2004 movie Kamikaze Girls, adapted from the 2002 light novel Shimotsuma Story- Yankee Girl and Lolita Girl by Novala Takemoto.

The story is about two teenage girls- Ichigo, the "yankee" or delinquent, and Momoko, the "Lolita". Both girls live in a semirural area in Japan, and are, in their own ways, estranged from the community around them. Ichigo, in keeping with her delinquent status, appears rough, tomboyish, and stereotypically "masculine" in her pursuits. Momoko, by contrast, appears delicate, ladylike, and stereotypically "feminine", as befits a Lolita devotee. However, the movie quickly makes it apparent that not all is as it seems. Under her rough exterior, Ichigo is a gentle soul seeking social acceptance, while Momoko is cold, withdrawn, and singularly focused. The movie ends with Momoko saving Ichigo from angry gang rivals, in a total reversal of the "damsel in distress" trope. The movie is constantly contrasting appearances v. reality, and questioning the validity of gender performance as a means of judging a person's personality.

As could be expected, Kamikaze Girls has a strong fan base in the Lolita community. Aside from the obvious enjoyment gained from seeing one's subculture featured on screen (along with the adorable old school Baby, The Stars Shine Bright outfits), I believe Kamikaze Girls resonates with Lolitas because it is a specific manifestation of the critique of gender performance Lolita makes in general.

Lolita is, in my opinion, a way to express femininity in isolation, or essence, without the cultural baggage. Unlike Momoko, most Lolitas are not "lifestyle", meaning they don't wear Lolita all the time. While most Lolitas will strongly denounce Lolita as cosplay, the truth is that it is an identity they assume- and take off- at will. The fact that there are male Lolitas- some of whom identify as cisgenderd straight- suggests that this is a "portable" femininity they can try on when it suits them. In the same way Ichigo and Momoko "balance" each other in the movie, I believe Lolita is a safe space for individuals to tweak and define their own gender balance. All people exist somewhere on a gender continuum, but it would be my guess that many Lolitas are more gender (and perhaps sexually) fluid than the society at large. Lolita gives people an "anchor" of femininity when they feel they need it, without encumbering them with the issues that surround more traditional aspects of gender performance in today's society. By making femininity an outfit you wear, it subtly critiques the notion of gender as a viable construct.

Friday, June 12, 2015

Tuesday, June 9, 2015

Lolita's Postmodern Appeal- Part I

What is postmodernity? That is a question I have been wrestling with since my graduate study days in the late 1990's. The best definitions I have seen focus on postmodernity's critique of the modern using pastiche, simulacra, and irony. Simply put, the postmodern is (was) a movement beyond the modern by taking pieces of the modern out of context, then reconfiguring it to create a not-quite-accurate recreation as a means of commentary or critique. For me, the postmodern is best understood through architecture, where the pastiche and ironic qualities are self-evident:

If you "get" this building, you "get" postmodernism. Look at all of those historical styles, jumbled together. Look at the outsized Ionic column at the center of the composition, just begging you to contemplate the centrality of Western culture and it's impact on the world we live in. And if this crazy trainwreck of a building doesn't make you smile (or at least shake your head in bemusement), you are truly dead to irony.

There are some who argue that we are beyond postmodern- "post-postmodern"- and in the larger society, this may be true. There is one place, however, that I believe the postmodern aesthetic and spirit live on, and that is the world of Lolita fashion.

Lolita fashion came about in the 1970's in Japan as an extension of the worldwide fascination with romanticized Victorian historical dress (think Gunne Sax here in the west)- and I contend- as an extension of the new postmodern ethic. It is no surprise that Japan was the home to Lolita, as their rich history of "cultural borrowing" made them supremely comfortable with cherry-picking the most appealing parts of western historical dress, and reassembling them into a frothy pastiche that bore the unmistakable mark of Japanese kawaii aesthetics. Lolita grew to worldwide fame in the 1990's- at exactly the same time postmodernism was reaching its zenith- and became recognizable as the fashion subculture that exists today.

Kengo Kumo, K2 Buildings, Building Tokyo 1991

If you "get" this building, you "get" postmodernism. Look at all of those historical styles, jumbled together. Look at the outsized Ionic column at the center of the composition, just begging you to contemplate the centrality of Western culture and it's impact on the world we live in. And if this crazy trainwreck of a building doesn't make you smile (or at least shake your head in bemusement), you are truly dead to irony.

There are some who argue that we are beyond postmodern- "post-postmodern"- and in the larger society, this may be true. There is one place, however, that I believe the postmodern aesthetic and spirit live on, and that is the world of Lolita fashion.

Lolita fashion came about in the 1970's in Japan as an extension of the worldwide fascination with romanticized Victorian historical dress (think Gunne Sax here in the west)- and I contend- as an extension of the new postmodern ethic. It is no surprise that Japan was the home to Lolita, as their rich history of "cultural borrowing" made them supremely comfortable with cherry-picking the most appealing parts of western historical dress, and reassembling them into a frothy pastiche that bore the unmistakable mark of Japanese kawaii aesthetics. Lolita grew to worldwide fame in the 1990's- at exactly the same time postmodernism was reaching its zenith- and became recognizable as the fashion subculture that exists today.

Top: "Otome" or maiden style from 1979- this is very in-line with the whole historical romantic/Pairie Style movement in the west (even though true "historical" Japanese maidens would have been rocking yukatas and kimono!)

Bottom: 90's Lolita from the pages of Fruits Magazine. Notice how "Gunne Sax-y" the top still looks. Both pictures are from this blog post, which is a great succinct history of Lolita.

Lolita has become much more than just a tweaking of western Victorian-era styles. Today, Baroque, Rococo, Empire, Regency, Edwardian, post WWII "New Look", traditional Asian, punk, and even 1980's children's wear influences can all be clearly seen in Lolita style. With all of that historical input, the resulting pastiche is not unlike the building above, in fashion form:

http://theheianprincess.tumblr.com/image/71857471294

She's wearing an Empire/Regency bonnet, very Rococo-esque sleeves and frills(including a faux stomacher of sorts), the print on the dress appears to be hoop-skirted Victorian ladies at a ball, done in a style reminiscent of children's "Holly Hobbie" bedsheets of the 70's-80's, on top of a poofy skirt held aloft by 50's New Look-esque petticoats that cuts off at the knees like an early 60's dress. Whew! If that doesn't make you smile, or at least shake your head in bemusement, you are truly dead to irony.

So, the pastiche/simulacra side of Lolita is pretty easy to understand. But, what about the commentary/criticism? Is the above outfit intentionally ironic, or did it just end up that way? I would argue that the look above is very intentional, and that ultimately, that is the heart of Lolita's appeal.

Before I move on, I would like to concede that every designer (and wearer) of Lolita is not making a conscious choice to incorporate elements from exactly the eras represented above, in exacting combination, to make a specific comment on society/fashion/women's roles, etc. In the same way that many pieces of postmodern art or architecture have been made as general commentary, or to appeal to a real, but perhaps unexamined impulse of the popular culture, so are many Lolita outfits a visceral interpretation of the zeitgeist of the 21st century global community from which they arise. That being said, for those inside the Lolita community, the commentary is profound, moving, and deeply embedded in the constant tension between their self-concept and the larger society's definition of their roles.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)